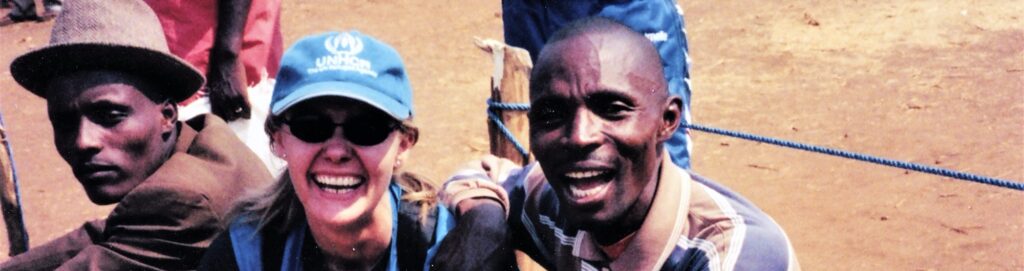

My mobile phone rang with a call from Burundi. Through static and whistling wind, I heard the voice of Kandinda, the Congolese vice-president of the Karurama refugee camp from where I had returned a few months earlier. We had worked side-by-side in Cibitoke, situated in the triangle between Congo, Rwanda, and Burundi, and very fast had developed an exceptionally close working relationship based on candid conversations and high trust.

The Great Lakes crisis was unique in its complexity, with local, national, and regional conflicts spilling over into Eastern Congo, and resulting in an estimated 3.9 million deaths. After the Rwandan genocide, the division of the Hutu vs Tutsi was revitalized here as Interahamwe, the paramilitary perpetrators of the genocide, escaped across the Rwandan border with all their arms. Additionally, the Burundian civil war spread to the area, and several surrounding countries continued to support armed groups in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Kandinda had fled to Burundi with 20,000 Congolese, to escape extensive ethnic clashes between armed factions resulting in large-scale displacement, particularly of Banyamulenge, a Tutsi ethnic minority. The majority did not have the necessary documents, so many chose to cross the Ruzizi River which separates Eastern Congo from Burundi, clinging on to empty jerrycans to stay afloat and hoping to evade the hippos inhabiting the river. Screams of women being attacked and raped by rebels tore from the bushes. Not all made it.

Leading a refugee camp was complicated, but Kandinda was street-smart, had the support of the community, and knew how to make things work in the camp. An exception was the initial great unease amongst the Pygmies, who left the camp every night to sleep up in the trees, fearful that the Tutsis would kill and eat them in their sleep. Having fled cannibalism in the forest areas controlled by the Mayi-Mayi tribal militias, who believed they would acquire strength and magical powers from eating specific body parts of the Pygmies, this danger felt very real to them. UN Peacekeepers surrounded the premises leaving the Pygmies feeling relatively protected despite leaving the camp itself. But also this situation was solved under Kandindas leadership and a sense of safety restored.

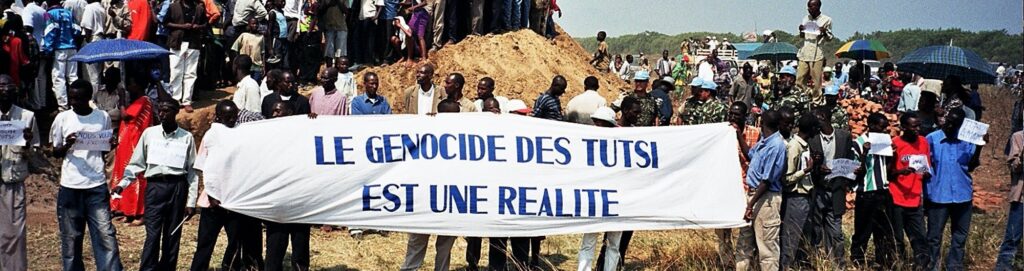

Shortly after, the peace was shattered. Armed men chanting religious songs and beating drums attacked a neighbouring camp in Gatumba at night. “There were songs, alleluias, same as those we sing in our churches. That’s why some trusted them,” a survivor said. A large, well-organized force of Interahamwe and Burundian Hutu dominated rebel movement, torched tents, killed people with machetes and gunshots, and left hundreds dead or wounded.

A few days later, before the CNN lens and the world media, bodies were buried in a mass grave. Some of Kandinda’s close family members were among them. The remaining camps along the border, including Kandinda’s, were closed. Refugees moved inland to a new camp located on a cold, isolated mountaintop in the hilly province of Mwaro, leaving them with little contact with their communities back in Congo. I could sense it took its toll on Kandinda, and his perpetually positive attitude was fading.

Once we had moved the camps, it was the end of my mission, and of an exceptionally close collaboration with Kandinda based on candid conversations and high trust. Having heard I was leaving Burundi, Kandinda came to say goodbye on my last day. Descending the mountain in the middle of the night, carrying a large handwoven lidded basket, he reached Bujumbura at dawn. The basket, he explained, was traditionally used at weddings to carry gifts and food. It was beautiful, and I felt humbled by his gesture.

Kandinda also had a question: could I take one of his youngest children back with me to Europe? He grinned. I smiled back and told him he knew the answer. He nodded, broadened his grin, and replied it was worth the try. We had a last chat, shook hands, and he left.

Months later on the phone, we exchanged a few greeting courtesies. How had he gotten my number, I wondered, and how was he able to make a long-distance call? There was a short silence on the otherwise scratchy line, and I asked how he was doing in the new camp. The conditions were poor, Kandinda confirmed. It was not an easy situation – but that was not his reason for calling, he added, as if he had read my thoughts. He just wanted to know if I was home safe and be reassured that I was doing well.

It was clear that he meant it. Kandinda told me to take care, and with the noise of the wind from the mountain, the call ended. We never spoke again.